Fluxus, Freedom, and Future Days: A Conversation with Irmin Schmidt

Zeki Hirsch - June 4, 2024

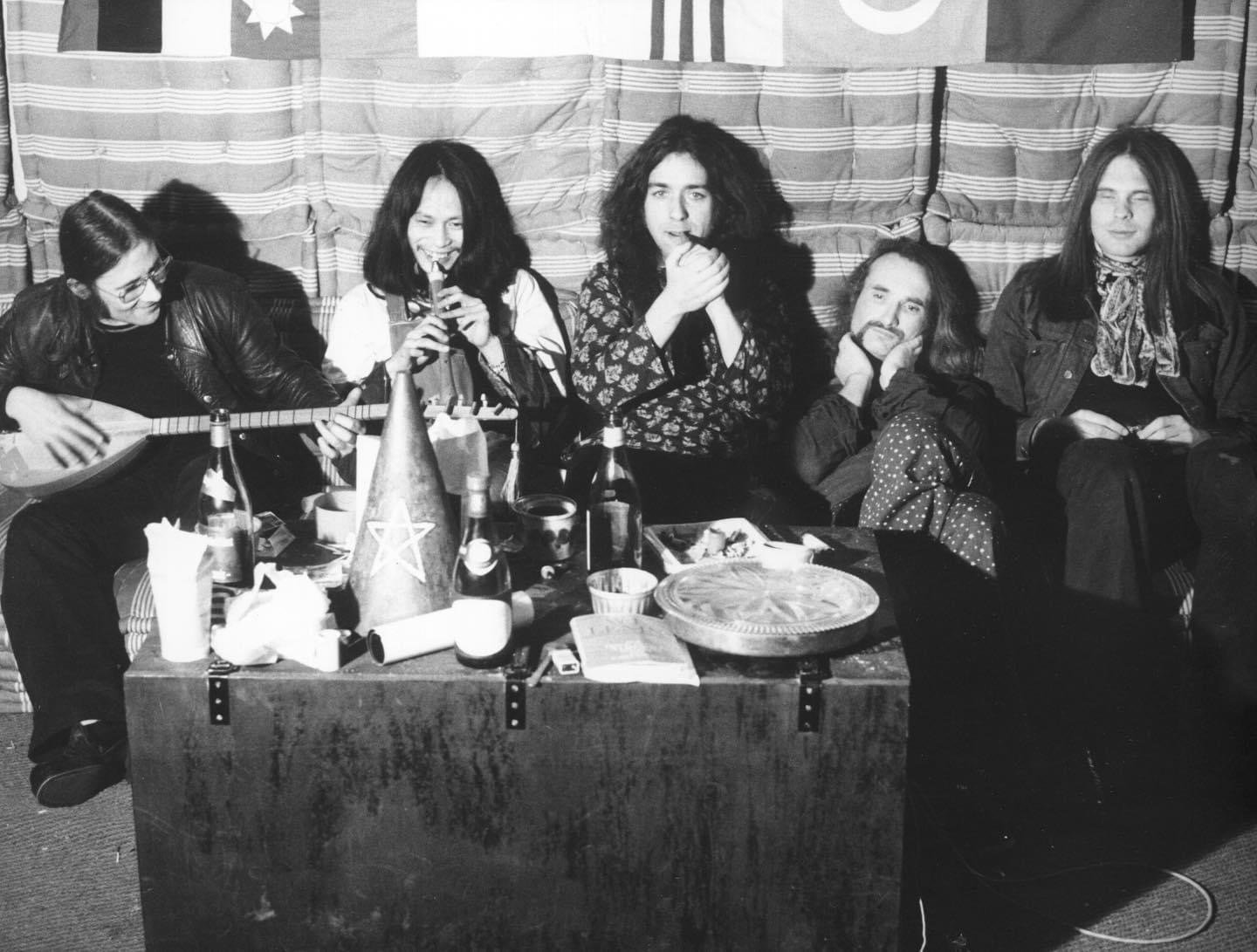

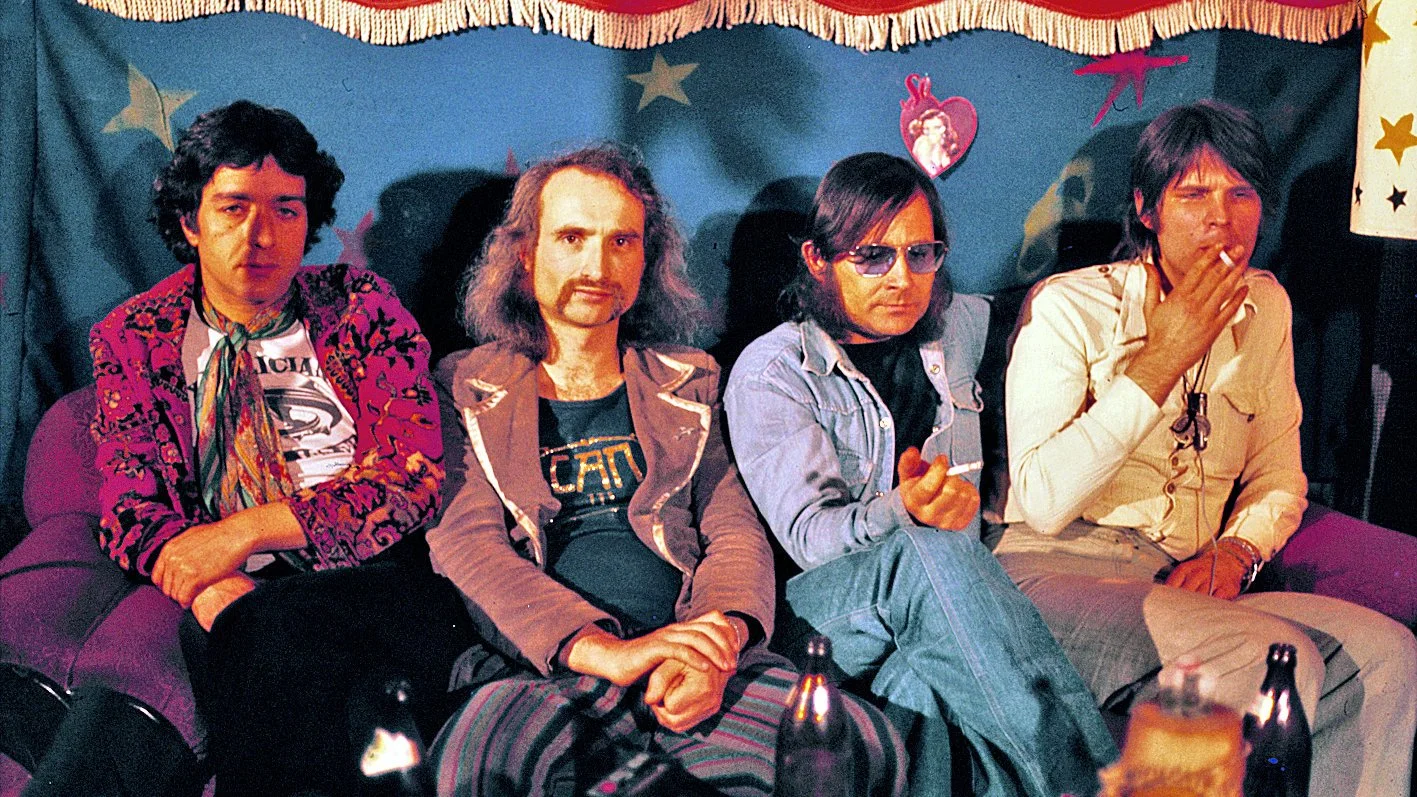

Can, 1972 (L-R: Irmin Schmidt, Damo Suzuki, Jaki Liebezeit, Holger Czukay, Michael Karoli).

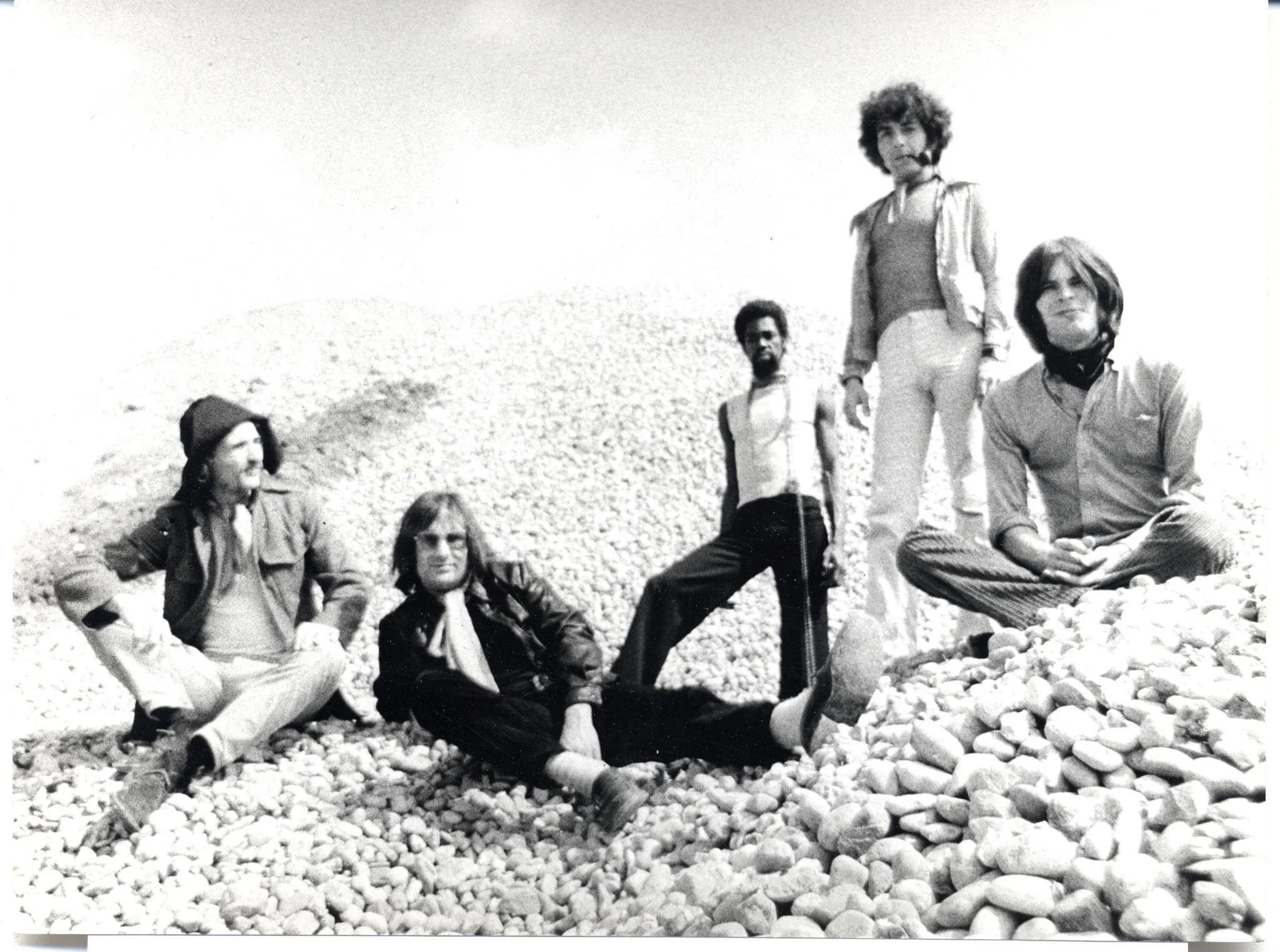

Irmin Schmidt is a sonic Dadaist. As the synth player for the legendary German band Can, which he co-founded in 1968 and remained with until their breakup in 1979, Schmidt helped spearhead some of the 20th century’s most daring and universally-revered music. Nearly sixty years after Can’s embryonic origins in Cologne, the sounds they created are still impossible to define. In the early 70s, British journalists came up with the vague, casually xenophobic label “Krautrock” to describe Can and their musical contemporaries as they emerged from the various countercultural pockets brewing within the ruined cities of West Germany. Although the name has stuck ever since, it’s particularly useless when it comes to Can. For starters, the group revolved around a quartet of formally trained musicians for most of its history. Schmidt, a pianist who studied under the experimental composers John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, was well-matched with Holger Czukay, a fellow pupil of Stockhausen and Can’s bassist. Czukay in turn brought his one-time music student, guitarist Michael Karoli, into Can’s orbit. Free jazz wizard Jaki Liebezeit was originally tasked by Schmidt with finding Can’s drummer, only to offer up his own services instead. Still without a singer, this eclectic cluster of classical and jazz acolytes first enlisted Malcolm Mooney, a Black American living abroad to avoid the draft, to be Can’s voice. Mooney sang on Can’s debut album, 1969’s Monster Movie, before departing that same year. He was replaced by Damo Suzuki, a Japanese busker who Czukay and Liebezeit first encountered on a bustling Munich street in 1970.

With a lineup educated in both European and American traditions of music and foreign-born singers with no musical training, Can embodies something far beyond “Krautrock.” On masterpiece albums like Tago Mago (1971) and Ege Bamyası (1972), the group exists as a mutated hybrid of James Brown’s cyclical grooves, Jimi Hendrix’s acidic riffs, and the audacious experimentalism of the Velvet Underground while Suzuki trills in an untranslatable amalgamation of English, German, and Japanese. These albums also include sprawling sound collages, comprised of tape tracks painstakingly pasted together, inspired by the more dissonant and exploratory compositions of Cage and Stockhausen. 1973’s Future Days, a tour de force of ambient rock, is dominated by both the gentle drone of South Asian music and relentlessly danceable percussion drawn from Turkey and the Arab World. A performance filmed at Paris’s Bataclan a few months before Future Days was released showcases the band at the height of its powers:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gIpzlS2xsUc

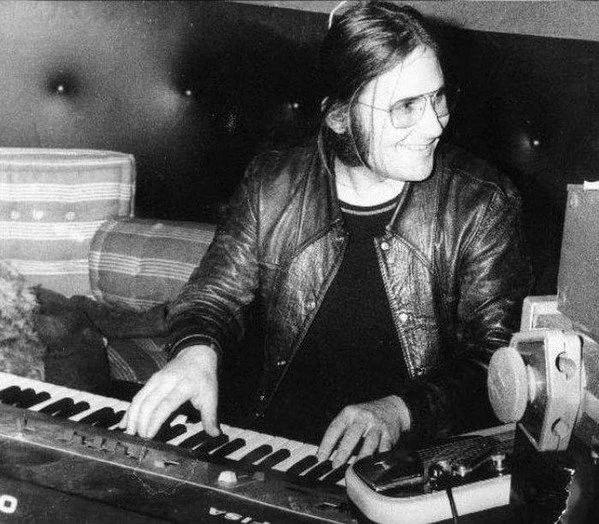

Shows such as these offer a glimpse into the inner workings of Irmin Schmidt’s psyche. Just like on Can’s albums, his synths and keyboards are often hidden beneath the searing parts of Czukay, Karoli, Liebezeit, and Suzuki for minutes at a time. Then, without warning, Schmidt cranks up every dial he can find, smashes his entire forearm into the keys, and unleashes a tsunami of feedback onto the audience. Like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain or Bicycle Wheel, Schmidt’s synth parts almost seamlessly blend into the audience’s surroundings before they jump out, grab us by the throat, and make their presence known. These moments, however, are secondary to the subtle flourishes and melodies that define Schmidt’s playing. “That is one big mystery of all art,” Schmidt once said, “that you leave space for the listener, the viewer or the reader.” It comes as no surprise, then, that Schmidt is a champion of visual art: from Germany’s pre-war Expressionism to the Fluxus movement of the 60s, Schmidt’s passion for visual art help situate Can within the broader history of the European avant-garde. Indeed, just as Duchamp’s works continue to perplex modern museum visitors, Can’s music pervades 21st-century popular music. Texas rockers Spoon named themselves after Can’s eponymous 1971 single, and the Killers used Future Days’ “Moonshake” to create the drum track for the 2020 song “Dying Breed.” Can is almost inescapable in hip-hop; Earl Sweatshirt, A Tribe Called Quest, and Tyler, the Creator are just a few of the artists who have sampled Can. Can was psychedelic. Can was funky. Can was musique concrète. Can was classical. Can was Krautrock. Can was not Krautrock. Can was a phoenix, rising triumphantly from the ashes of Nazi Germany’s genocidal horrors and sparking an eternal flame that will burn long after our earthly bodies fail.

Today, Irmin Schmidt is one of the last men standing. Michael Karoli died in 2001, Jaki Liebezeit and Holger Czukay both died in 2017, and Damo Suzuki died in February 2024. Malcolm Mooney — now devoted to painting and poetry — continues to make sporadic musical performances, but it is Schmidt who is the greatest link between Can’s existence as a musical phenomenon and as an artistic phenomenon. As someone equally obsessed with Can and art history, I see Schmidt’s steadfast commitment to the band’s live archive as a new way to experience Can as collage: an ongoing series of live albums splices together decades-old cassette recordings made by fans, using different tapes to magically reconstruct individual episodes of the band’s untethered energy before 70s audiences. The most recent installment, Live in Aston 1977, was released on May 31st. I spoke to Schmidt about his experiences in the worlds of music and visual art and found myself just as enthralled as when I first listened to Tago Mago. While art and music exist in different psychic spheres for Irmin Schmidt, it is clear that they have both helped define the essence of who he is.

Zeki Hirsch: You were born into a world where the avant-garde was under attack in Germany. Arno Breker and Albert Speer were the artists being put on a pedestal, while Max Beckmann and Otto Dix were called degenerate. As a child, what were your formative experiences with visual art?

Irmin Schmidt: Until I was eight years old, I had a big part of my childhood in Austria and the country. We were from Berlin, and families with kids were evacuated into the country, [where] there was not much art. Sometimes my mother went with me to Salzburg. Salzburg is full of wonderful Baroque architecture, and she showed me all this and went with me into castles and palaces and churches. After coming back to Germany, I came into a totally bombed city, and there was no visual art. When I was about 14, I had my closest friend, and while we were both in school, I was making music and he was painting. It was this friend with whom I experienced visual art for the first time. Not this Nazi stuff, but we discovered Beckmann and Schmidt-Rottluff and Klee, these paintings. And, actually, that was the first time I went to a museum. The museum was bombed too, so there was little to see. The very first strong experience [with art] I had was in this town, Dortmund. In Dortmund’s museum, there was a show of Giacometti for the first time, and I went crazy. Every day after school, I went to the museum and sat down on the floor and stared at one of his sculptures until the director of the museum came in and — because they were afraid I'm crazy — she asked me why I was sitting there every day for hours, staring at the sculpture. I think that was one of the very first experiences where I really got totally lost into an art experience.

Can, ca. 1969 (L-R: Holger Czukay, Irmin Schmidt, Malcolm Mooney, Jaki Liebezeit, Michael Karoli).

Irmin Schmidt, 1970s.

Can onstage in Hamburg, 1972 (L-R: Holger Czukay, Jaki Liebezeit, Michael Karoli, Irmin Schmidt).

ZH: And how did that change when you were in Can? I know that you were a fan of Cy Twombly as well. How did your visual art experience start to change as you were playing music and getting a little older?

IS: Hard to say. Besides reading, going to galleries and museums was like daily food. I needed it! Twombly I discovered in an exhibition, when he was still totally unknown. Even my painter friends didn't like him. This was early, when he was scribbling with pencil and little colors on canvas. I became totally fascinated. I still am. I have a little book with paintings of Twombly in my studio, right beside the desk. Sometimes I look into it, but I don't know how it influences me. It does somehow, but I wouldn't say I want to make music like Twombly paints. It's just part of my imagination.

ZH: That makes sense to me. I would say [something like] the Can Free Concert was almost an artwork in and of itself since your sound got messed up and you had to overdub things in the studio [which was filmed and integrated into the concert footage]. But also the way you hired circus acts to perform while you guys were playing, to me that almost feels like both a visual collage and and a sound collage.

IS: Of course. Collage is a keyword in 20th century art in every aspect, even in literature. Collage was for me, in music, a very natural thing. When we started Tago Mago, for instance, some pieces — “Aumgn” and all the rest — are pure collage. It may be that knowing about it from visual arts influenced me, but I don't think in a synergetic way and transform pictures into music. I never have, and when I make music, I don't think about pictures. But of course, there’s this very intensive occupation with visual art that had an enormous influence on me.

ZH: Tell me more about your relationship with Fluxus.

IS: That was in the mid 60s and late 60s. In Cologne, where I was studying with Stockhausen — who detested Fluxus — it was around me more or less, because Cologne was one of the main hotspots of Fluxus. Going to galleries, I saw a lot of performances by [Nam June] Paik. I was very, very attracted to Joseph Beuys. I love his drawings. At that time, Fluxus was something which seemed to be spontaneous; it wasn't that much. But it had nothing to do with the normal art business and world, it was very revolutionary, and I was very attracted by these performances. I made some myself. I once took part in an event where several artists were performing for 24 hours. Charlotte Moorman was there, naked, playing cello, wrapped in transparent cellophane. Then all of a sudden, she fainted. Paik and I unwrapped her, because I think her body didn’t get enough air. That was not planned as a performance, but it was a very exciting moment. She came back to life and everything was okay. There was something enigmatic about these performances, like haikus. You do one thing again and again, and after some time this very banal thing becomes mysterious. I knew Wolf Vostell very well because we were neighbors. At this performance, he had a big lump of raw meat and for 24 hours, very concentrated, he was putting needles into it. If somebody does that with all his concentration, they seem to be totally taken by it. There is this absurdity about Fluxus that was sometimes very funny and interesting. I still like it.

ZH: As someone who studies art and music, it feels as though Can is much more informed by art and visual movements and culture than a lot of other bands.

IS: My passion for visual arts, for paintings, for sculpture, might have influenced the other members, and the thinking of collaging — of putting pieces [of recorded music] together — was basically an influence from my side. But actually, the others weren’t very much into visual arts like me. The common feeling was the way we make music together, of creating spontaneously. It's hard for me to find the influence of visual arts on our and on my music. Even now, I'm just finishing a new record, and somebody said he saw a picture [while listening to it]. When I made it, I didn't see any pictures. I see no noticeable image during making music, and I think with Can it was more of an emotional thing. I get very, very emotional at exhibitions, but this emotion is what’s transforming into music.

ZH: Tell me more about your new record.

IS: The record is done, but I have to make a final mix. But it's also very collage-sounding — it’s l’art brut. I’m using sound from nature around me. I don't [modify] it, but I collage it with other things. Do you know the records 5 Piano Pieces and Nocturne?

ZH: Yeah.

IS: “Yonder,” the piece [on Nocturne], is really a collage of sounds of bells and sounds in the tower of the mechanism. There's nothing I add; I just keep it like it is and put it together with the piano sounds. That's something I love to do more and more in collaging: letting things like they are — brut — without any treatment.

ZH: And, I guess kind of related to that, you talk a lot about the relationship between music and ritual, especially in regard to the trancelike repetitions in Can. Could you tell me more about where you see ritual fitting into your music and music as a whole?

IS: Think about this: any kind of rock performance has something ritualistic about it. Any musical performance, especially in our culture, has something about ritual. A concert where there are people on stage, or even a symphony orchestra, are rituals to perform. It has nothing to do with religion, but music is a kind of ritual. It [is part of] the very ancient history of making certain rituals to understand the world. That’s what art is about — art is trying to make us understand the world from a certain angle, and ritual is an explanation to repeat the process of creating. It's all about creating, and creating is ritual.

ZH: I think it's interesting that you said that when you make and play music, there's no image that comes to your head. People often talk about Future Days as painting a landscape through sound, creating an image of the coast of Portugal. Since Michael was on vacation there, maybe that was more him, but I’ve always thought of Future Days almost like a romantic painting within an album.

IS: Well, it is the equivalent to paint. Creating soundscapes is a thing in itself; it’s not trying to describe via sound what you can also paint or imagine as a landscape or a picture. Any kind of music is, in a way, sound images, but it’s so difficult to formulate in words what music is. When I'm creating music, it's purely musical, but then people listening to it will try to translate what they hear into something they can talk about, and they talk about landscapes. This is an interpretation of what you hear, but it's not what the music is, because describing music is impossible. Interpretation is obviously a need because our communication function is language, so we try to translate everything, even visual arts. I’ve heard millions of interpretations of pictures which try to explain to me what someone has seen, but try to explain in words what a Basquiat painting is. In a way, it’s absolutely impossible! You can describe your emotions in front of a painting, but this doesn't describe the emotions the painter had — if he had any — during painting the picture. It’s the same with the music. There are so many interpretations trying to explain a Beethoven symphony, but in the end, it's music, which you can't put into words.

ZH: I was wondering if you could say anything about the cover art for the Can live series. I've been really fascinated by how it shows the band’s speakers with animals and plants. Why did Spoon Records choose to go that route for the cover art?

IS: The artist is a woman [Uschi Siebauer] who is a very close friend of our daughter [Sandra Podmore], who works in Spoon Records. They studied film together and when it came to making covers for the live series, Sandra said, “Why not ask her to make the covers?” because she makes beautiful art. She had a proposal of this loudspeaker thing, and I really liked it. There was no long discussion about it; we all said it’s a good idea which can continue for the whole series. [The cover art] can have a lot of variations, but the basic image stays the same. I think that cover art just happens. There was never a long plan for Can’s or my own work. There was somebody who said “why not like this?” and then you talk about it, you change it a little bit, you have alternative ideas, and finally it happens. For the live series, it was a very quick decision. Her first ideas with these loudspeakers, letting them be inhabited by strange creatures, I really liked that. I think it fits.

ZH: It's very fitting. It's also not like any other album cover for a live series that I've ever seen.

IS: Yeah, I really thought it was quite original. It has something alien on one side, and also this kind of strange monumentality. At the same time, there is something mocking about it. There's a sort of irony in it, which I very much like. It's ironic, but at the same time, it's very mysterious.

ZH: For me, there's almost a woodcut aspect of it, like in the Nuremberg Chronicle, or Dürer’s woodcut of the rhinoceros. It very much reminds me of that as well.

IS: Good! [laughs] I haven't thought about that. I have to ask her if she had that in mind. It’s sort of what I liked about it — in a very hidden way, it had something to do with German tradition, German history. It transports a very faint idea about our history, which of course is something that Can is very much connected to. The elements of our music go a very long way back into early European music.

ZH: And back to the Stone Age sometimes.

IS: [laughs] Yes! That was especially Jaki’s passion. He never talked about it much, only very little sometimes, but he had actually just learned Sanskrit and was quite into the old Indian Vedas and Upanishads. So talking about ritual, this is the most ritualistic culture that has ever been on Earth. [The Italian writer] Roberto Calasso wrote a fantastic book about Vedisch culture [Ardor].He also wrote a book about Tiepolo [Tiepolo Pink]. I love Tiepolo very much — he is kind of the inventor of comics. There is this castle in the book [Würzburger Residenz in Bavaria] with these wall paintings, which are absolutely fascinating, from the 18th century.

ZH: I noticed that you occasionally speak about Can in a Marxist context. You've mentioned that you wanted Can to own its production means, even if that meant having more limited recording equipment. I was wondering how else you see Marxism impacting your music with Can or as a solo artist?

IS: Marx was pointing out that the ownership of the production means makes you free and prevents you from being dependent. But [with or without Marx], we had the idea to be independent from the industry and from managers. That's why we said we’d record with a two-track, two-way boxes, and that’s it. It's a matter of being independent from people who tell you what to do. It's a kind of Marxist idea, but Can didn't care about theoretics. It was just a practical way of doing things. There was never a discussion about what should be done because of a political situation. We wanted to make this kind of music, and we didn’t want anybody to tell us how it has to be in order to function or in order to have a market. We didn’t go into commercial studios because we didn't have any money. A record company might pay [for studio time], but they already had certain ideas of how it should be done. To avoid all that, we did it our way. Of course, it is political, but there were no theoretics ever.

Can, 1973 (L-R: Irmin Schmidt, Holger Czukay, Michael Karoli, Jaki Liebezeit, Damo Suzuki).

ZH: I think that's a much better way of looking at it. It makes everything more stable. I think once you get into politics too much with music, it becomes a little more unstable. There are more pressures on it.

IS: To avoid any pressure, you have to accept that you're technically [limited]. Strangely enough, it turned out that everybody thought that Can’s recording quality, with the very little means we had, created a fantastic sound because there were no technical tricks. It's just the basic microphone and recorder, but nothing else.

ZH: You studied under John Cage and performed his music as well. Tell me about your experience playing pieces like 4’33”.

IS: I performed quite a lot of Cage, even “Atlas Eclipticalis” with a symphony orchestra as a pianist, and I performed this piece of silence [in the 60s]. It's less a musical experience than it is a very emotional, strange moment. People expect you to play because it's announced as a piece, and then you don't do anything for four minutes and a half. As a pianist, the most interesting part of the piece for me was sitting there motionless and listening to what happens in the public. If you listen to the public, and if you really do nothing else, amazing sounds appear. People try to make no sound and all of a sudden breathe differently than they normally do, or try to suppress laughing. They start silently laughing, because this is an uncomfortable situation for some people. It’s very Freudian. I performed 4’33” maybe six or seven times. I wish I had recorded this because every time I performed it, it was framed by two other pieces — like Messiah or something — where people really get something exciting, pianistic to listen to. All of a sudden, you do nothing, and the sounds in the public are amazingly interesting! In certain cases, you hear something from outside. [During a performance of 4’33”] in Summer, it was very hot. In the hall, there were windows. Somebody opened a window, and the sound from outside was pure music. There were traffic sounds far away. That's a classical thing for this piece: all of a sudden, what you experience is the sound a certain number of people produce when they are confused. And that's very interesting.

Can, 1974 (L-R: Jaki Liebezeit, Holger Czukay, Irmin Schmidt, Michael Karoli).

Irmin Schmidt

The author wishes to thank Irmin Schmidt, Sandra Podmore, and the entire Spoon Records family for their incredible help and patience, without which this piece could not have been written. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.