Exhibition Review: “Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt”

Katy Kim - March 6, 2023

Lintel Fragment Depicting Iniuia and Iuy Worshipping Deities (1336-1327 BCE), limestone and pigment, Art Institute of Chicago. Currently on view in the exhibition “Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt.”

One of the largest and oldest museums in the United States, the Art Institute of Chicago’s special exhibition "Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt" (2022) offers a critical opportunity to study how a leading art museum has approached their recent display of Ancient Egyptian art. Highly anticipated, the exhibition represents the Art Institute’s first new installation of ancient Egyptian art in a quarter-century. Museums are powerful socio-cultural institutions, yet face the business imperatives of garnering annual attendance, funding, and donor support. Still, museums’ exhibitions of Egyptian art have been overwhelmingly popular, seen through attendance rates at iconic blockbuster exhibitions like that of King Tut. Yet, as art historian Elizabeth Marlowe notes, modern museums continue to face larger “questions of subjectivity, epistemology, transparency, accessibility, and responsibility to the wider community,” particularly regarding museums’ display of ancient art.1 Therefore, I was curious to understand how the Art Institute of Chicago’s special exhibition "Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt" might navigate its recent presentation of Ancient Egyptian art this past fall. Overall, I thought that while the exhibition attempts to address some historical issues of display; its spatial dynamics, engagement with its theme, and use of didactic materials overwhelmingly fail to present a reinvigorated presentation of Ancient Egyptian art. Instead, the exhibition’s resounding impression is one of ambiguity—not enough material is contextualized, and these curatorial silences fail to truly challenge popular preconceived notions of Ancient Egypt.

The exhibition’s spatial orientation attempted to create new viewing experiences highlighting the objects’ formal qualities, but I thought the curators did not utilize the physical space well. Upon entering the Art Institute’s main entrance, marketing material for the special exhibition was absent, with no signage indicating how prospective viewers might find the exhibition. After asking a security guard, I was finally instructed on how to locate the exhibition: one must first traverse through the entirety of the “Arts of Asia,” which comprises works of Hindu and Buddhist sculpture, Chinese jades, and Japanese screens and woodblock prints. Afterwards, a visitor is directed to take a nondescript set of small stairs on the right. Signage is minimal, and the sole banner near the exhibition advertises another exhibition, “The Language of Beauty in African Art” (2022), which is located above it (Image 1). By placing the "Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt'' near Asian Art and African Art, the curators suggest relevant connections between Egypt and other parts of the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA); however, the lack of permanent signage diminishes Ancient Egypt’s distinct position alongside these two geographic behemoths. Finally, the long path to reach the exhibition and the necessity of stairs may pose barriers to museum visitors who may be differently abled and less familiar with the space.

Image 1: Exhibition Signage

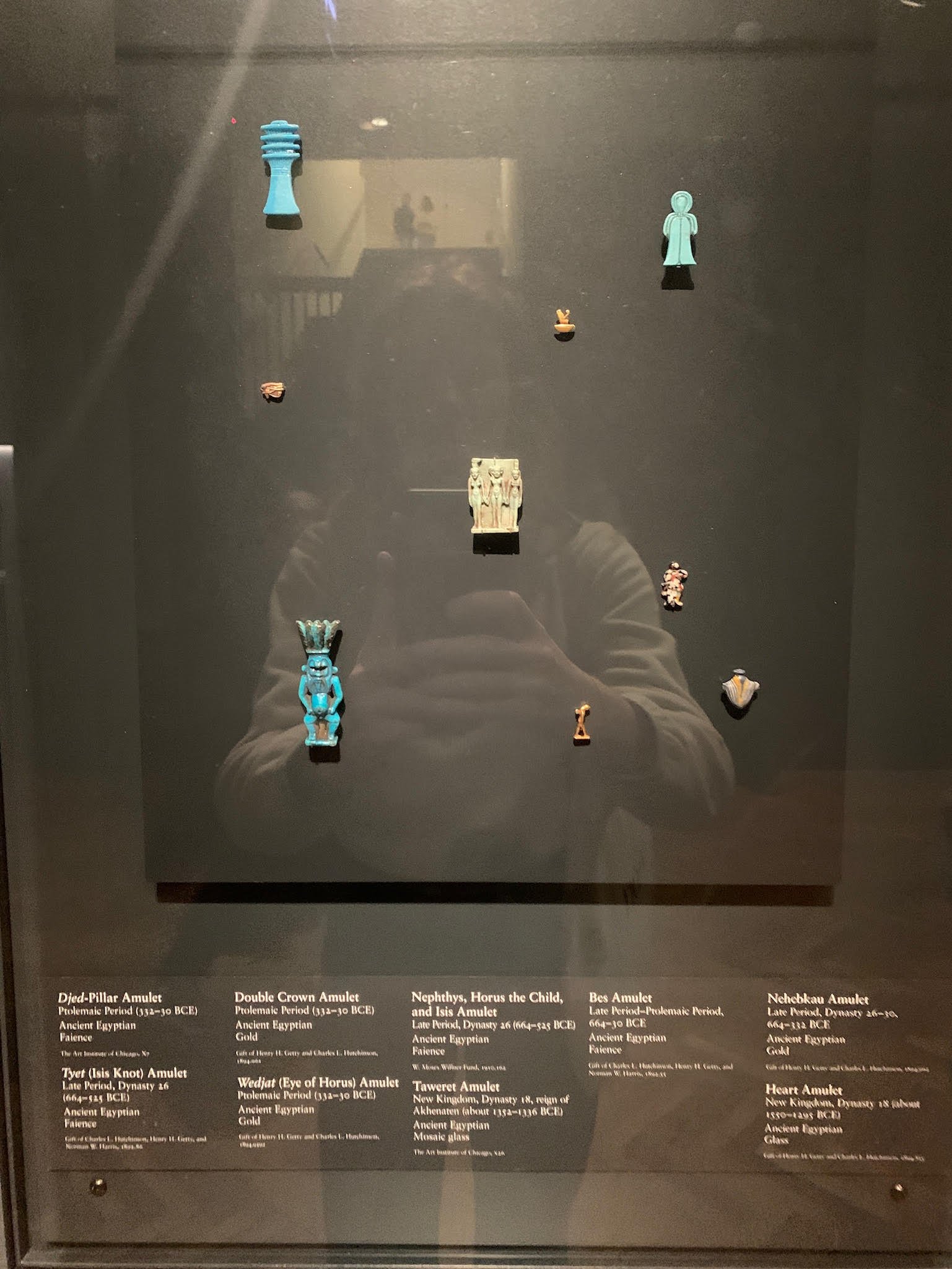

Entering the exhibition, I immediately noticed that the room where all of the objects are displayed is extremely long and narrow, which only offers visitors one preordained path to view the art objects (Image 2). There is a striking absence of wall texts, including an introductory wall text, leaving a viewer uncertain (as I was) of which side to begin their journey at. I do commend the exhibition’s use of color, however—all the walls are painted with a deep slate, which lends the environment a sense of elegance and solemnity while simultaneously allowing the material properties of each object to stand out. For example, a turquoise Djed-Pillar Amulet (332-30 BCE BCE) crafted from faience was noticeable for its striking color (Image 4).

Objects are grouped tightly together and housed in glass display cases that were adhered on the wall. These individually illuminated glass cases allowed viewers to study each object clearly through the glass, while protecting these objects from visitors, humidity, and temperature. Oddly, the Art Institute describes these cases as promoting the ability to view the art from multiple points of view: “Striking artifacts—displayed along one wall of the gallery in a series of innovative cases that promote viewing from multiple vantage points.”2 Yet, as the glass cases were organized on one wall alone, viewers could only walk down one path and view them in a straight line. Due to how tightly the cases were placed to each other, I was unable to view most of these objects from any other vantage point besides from the center. While the exhibition attempted to cultivate new viewing experiences through transparent display cases and the wall color to highlight objects’ formal qualities, I thought that the space prevented dynamic opportunities to engage with the objects from multiple perspectives.

Secondly, I thought the exhibition’s engagement with the theme of "Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt" was unsatisfying, with most of the objects relating to death, rather than life. As Ancient Egypt’s presentation with public audiences has primarily been mediated through the frame of death, viewed through blockbuster exhibitions like that of King Tut,3 I was looking forward to seeing how the curators might convey nuance, depth, and balance to their presentation of Ancient Egyptian culture. Returning briefly to explain the exhibition’s organization, the curators’ presentation of objects started with ‘life,’ represented through a series of statuettes; for example, a Statuette of Sobek (664-332 BCE, Image 3) points out the Sobek’s association with fertility and the Nile River. Then, the exhibition addresses the theme of death for the rest of the exhibition, and concludes with the mummy of Pa-ankh-en-Amun. Instead, as a viewer, I would have appreciated organizing the objects around thematic foci, and a more balanced integration of different objects representing both life and the afterlife instead. Finally, after viewing the mummy of Pa-ankh-en-Amun, I was abruptly led to two final display cases and the stairs, without concluding exhibition text to fully contextualize my experience, and the theme.

Located at the exhibition’s end, the mummy of Pa-ankh-en-Amun, an Egyptian man who lived around 900 BCE, was presented in the only independent nook of the exhibition. Prior to entering where the mummy was housed, visitors were met with a small amount of wall text that shared that they would be encountering a mummy (Image 7). The curators’ decision to house the body in a distinct area of the exhibition with a separate label was effective, as it encouraged viewers to cultivate a different state of mind when viewing the mummy, and offered an option to opt-out of viewing it. In particular, the digital tablets on the left side of the mummy offered important details of Pa-ankh-en-Amun’s identity in, “Pa-ankh-en-Amun and his father held the position of Doorkeeper in the Temple of Amun” (Image 8). The unobtrusive tablets (which were also successfully employed in other areas of the exhibition) allowed visitors to access digestible pieces of object-based information without visually detracting from the artifacts on display. These details were also available online, allowing for broader public access.

However, visitor photography was still allowed of Pa-ankh-en-Amun, which was not supportive in creating an environment of deep reflection and recognition of the dead. There was also a noticeable lack of information on how the mummy had been acquired by the Art Institute itself—which was a missed opportunity to address pressing issues of provenance, repatriation, and care. While the exhibition feebly attempted to counterbalance dominant popular depictions of Ancient Egypt, as associated with death, the curators’ rather simplistic organization of objects and display of Pa-ankh-en-Amun did not fully address the issues of provenance or spiritual care to meet their goal.

The Art Institute of Chicago’s didactic materials (i.e. wall texts and labels) were also absent of information on essential historical context. The exhibition itself was conspicuously devoid of wall text, save for two general panels of information. One panel was titled “Life in Ancient Egypt,” and the other, “Afterlife in Ancient Egypt.” There was no introductory wall text to frame the exhibition, nor closing text of the exhibition, as discussed above. These silences, as conveyed through a lack of didactic materials and information, left viewers unclear on the exhibition’s themes, goals, and the organization. Furthermore, I thought the missing introductory text implicitly concealed institutional details including who had curated the exhibition, who funded it, and where the displayed objects had come from. With this lack of wall text in mind, I will discuss the sparse labels that operated as the primary means of communication below.

In particular, I’d like to discuss a grouping of five different plaques: a Plaque Depicting a Ram (332-30 BCE), Plaque Depicting a Quail Chick (332-30 BCE), Trial Piece with Hieroglyphs (ca. 300 BCE), Double-Sided Plaque Depicting a Lion and Birds (332-30 BCE), and Plaque Depicting a Queen or Goddess (332-20 BCE). These objects were mounted in a staggered order, while corresponding labels were organized linearly below the objects, which made it difficult for museum visitors to understand which label actually applied to each object. As a result, I thought the exhibition seemed to privilege a visitor with prior knowledge of different artistic materials to correctly identify which object corresponded to each label (Image 5).

Image 5: Plaque Grouping

The tombstones also lacked detailed information on the provenance and acquisition history of each object. Of note, the only information on the Plaque Depicting a Queen or Goddess reads ‘Museum Purchase Fund.’ Given how neatly the plaque itself looked cut out, I had unanswered questions on how the object was acquired by the museum, inspired by Marlowe’s discussion of Vesuvian fresco fragments at the Getty Museum.4 Instead, the curators’ silence regarding the original viewing contexts of the objects spoke volumes, and their presentation gave the impression that the objects had almost been there all along. In terms of accessibility, the Art Institute of Chicago could also number their labels to which objects they corresponded to and add a small image on each label, following the Getty Museum’s example.5 Curators also might share the names of the museum professionals who contributed to each label text to encourage visitors to learn more and also consider the subjectivity behind the institution’s label-writing process itself.

In closing, the Art Institute of Chicago’s recent exhibition "Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt" (2022) is significant for study on display practices of Ancient Egyptian art, given critical discussions on transparency, multiple perspectives, and contextualizing museum presentations of historical artifacts. I found the most effective components of the exhibition to be its use of digital resources, the isolation of particular objects, and minor improvements on presenting the mummy Pa-ankh-en-Amun. Still, I felt that the exhibition should have used a more integrated spatial organization to better convey the connectedness of life and death, implemented changes to clarify didactic materials, and proactively communicated institutional information on provenance, curators, and funding. To conclude, I thought the exhibition failed to provide a truly renewed presentation of Ancient Egyptian objects that fully conveyed their history, context, artistic value, and cultural significance. Ultimately, museums’ presentation of culturally-loaded Ancient Egyptian objects is a complex topic; only will the critical evaluation of museum practices contribute to more nuanced exhibitions.

Notes:

1 Elizabeth Marlowe, “The Reinstallation of the Getty Villa: Plenty of Beauty but Only Partial Truth,” American Journal of Archaeology 124 (2020): 326.

2 Art Institute of Chicago, “Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt,” 2022. https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/9761/life-and-afterlife-in-ancient-egypt

3 Meredith Hindley, “King Tut: A Classic Blockbuster Museum Exhibition That Began as a Diplomatic Gesture,” HUMANITIES 36, no. 5. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2015/septemberoctober/feature/king-tut-classic-blockbuster-museum-exhibition-began-diplom

4 Marlowe, “The Reinstallation of the Getty Villa,” 322-28.

5 Marlowe, “The Reinstallation of the Getty Villa,” 327.

Bibliography:

Art Institute of Chicago. “Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt.” Art Institute of Chicago. 2022. https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/9761/life-and-afterlife-in-ancient-egypt

Marlowe, Elizabeth. “The Reinstallation of the Getty Villa: Plenty of Beauty but Only Partial Truth.” American Journal of Archaeology 124 (2020): 321-32.

Moser, Stephanie. “Legacies of Engagement: The Multiple Manifestations of Ancient Egypt in Public Discourse.” In Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures, edited by William Carruthers, 242-52. London: Routledge, 2015.

Hindley, Meredith. “King Tut: A Classic Blockbuster Museum Exhibition That Began as a Diplomatic Gesture.” HUMANITIES 36, no. 5 (September/October 2015).